T cell development and selection throughout the lifespan

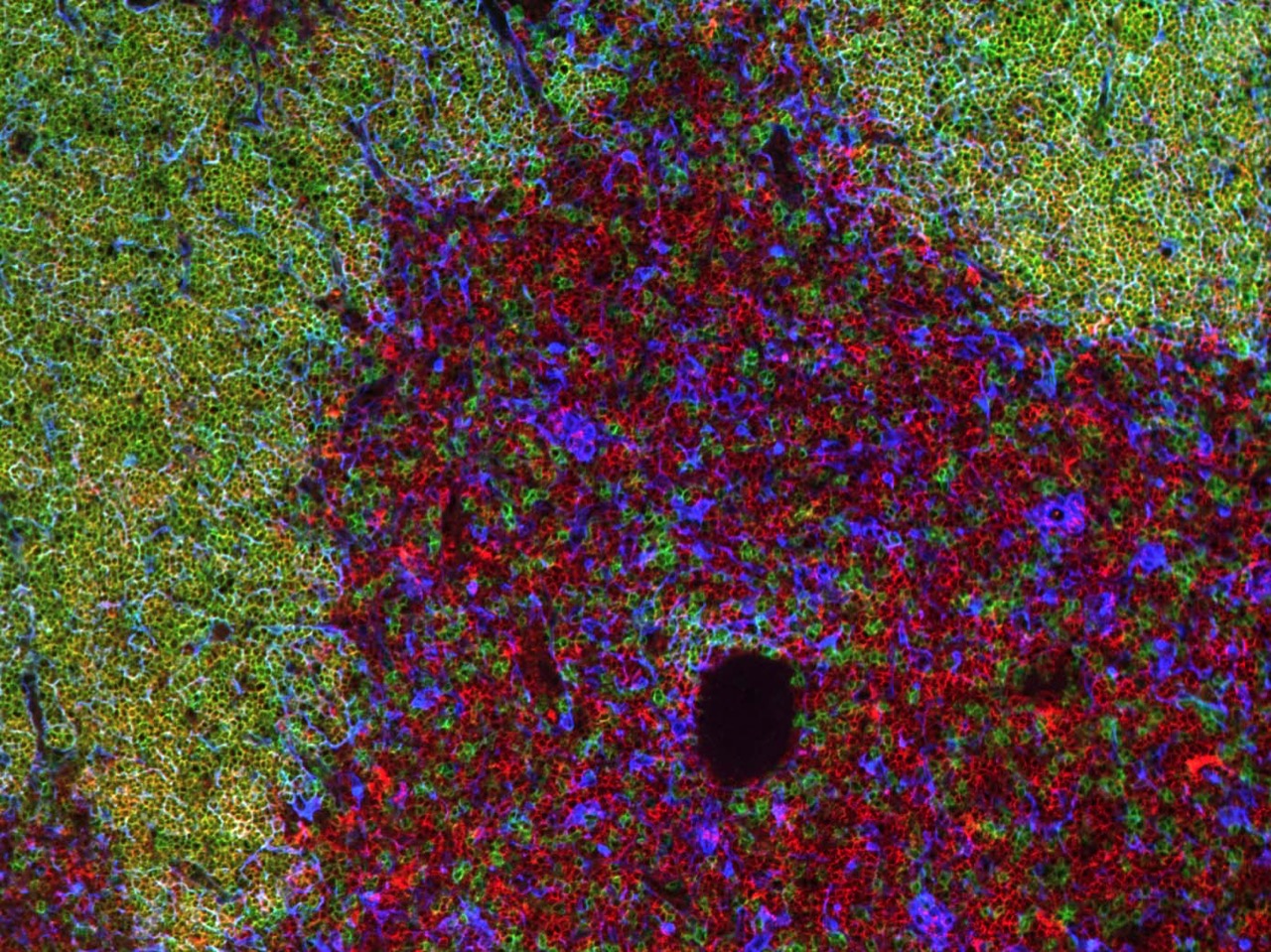

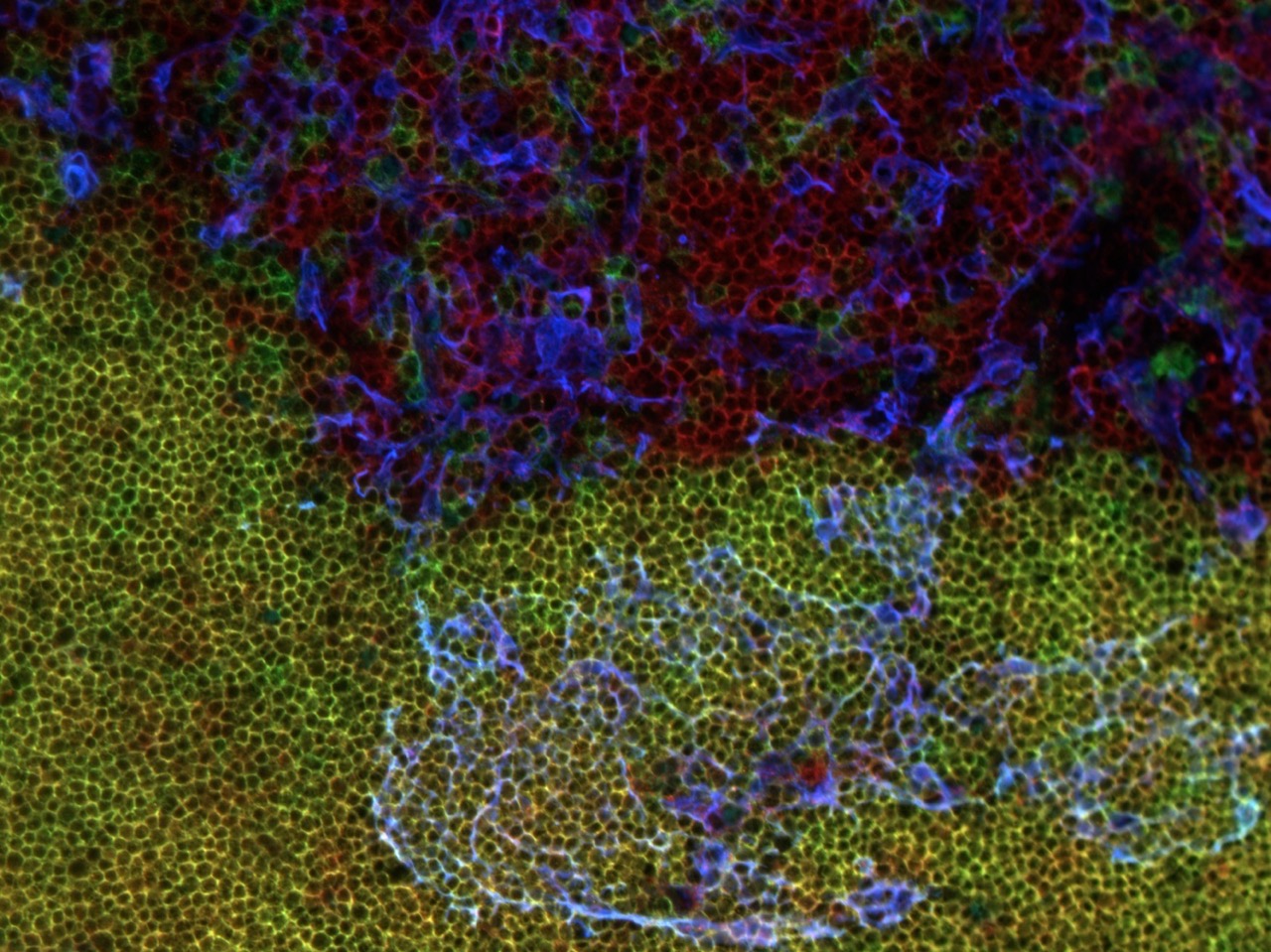

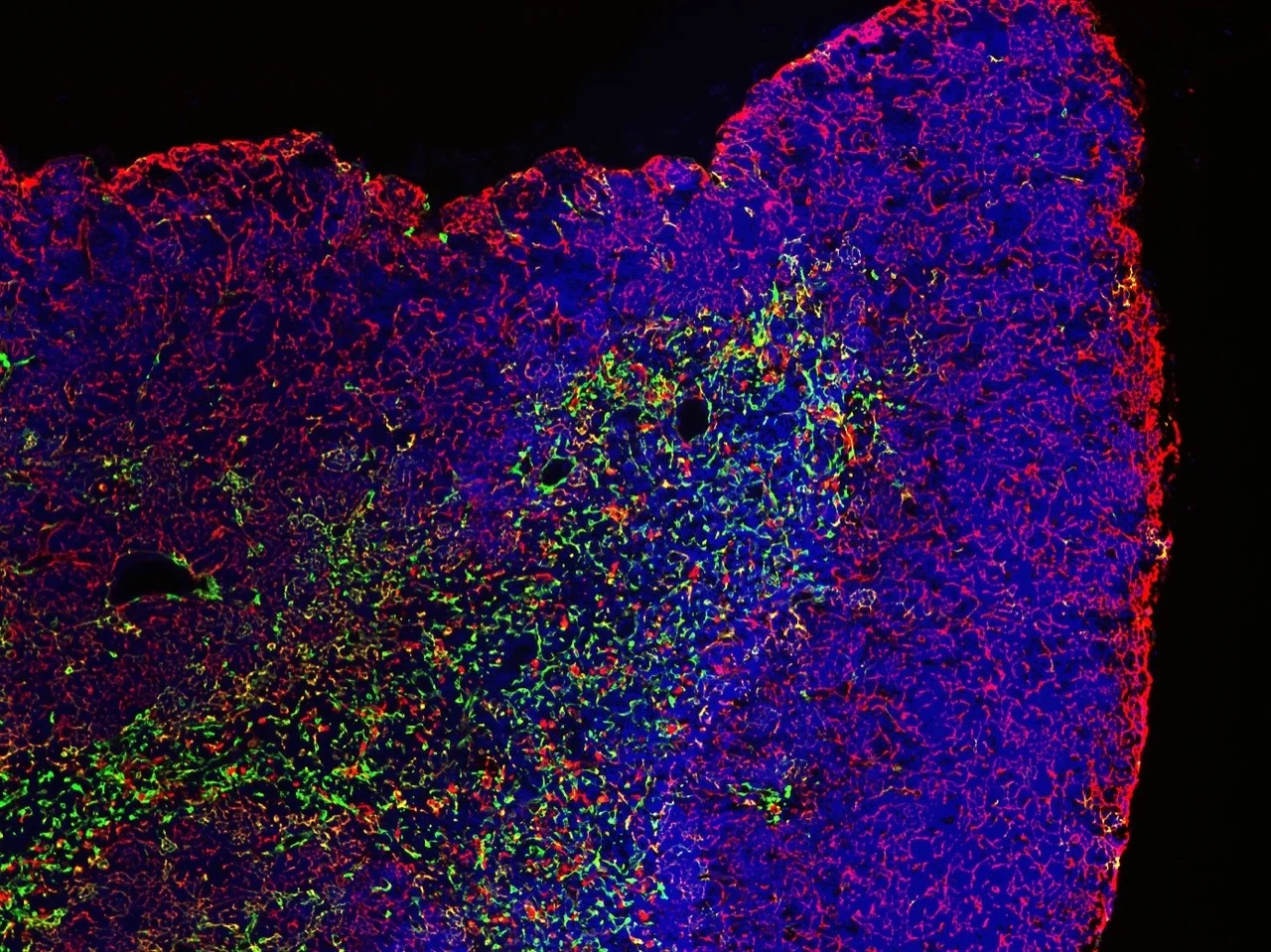

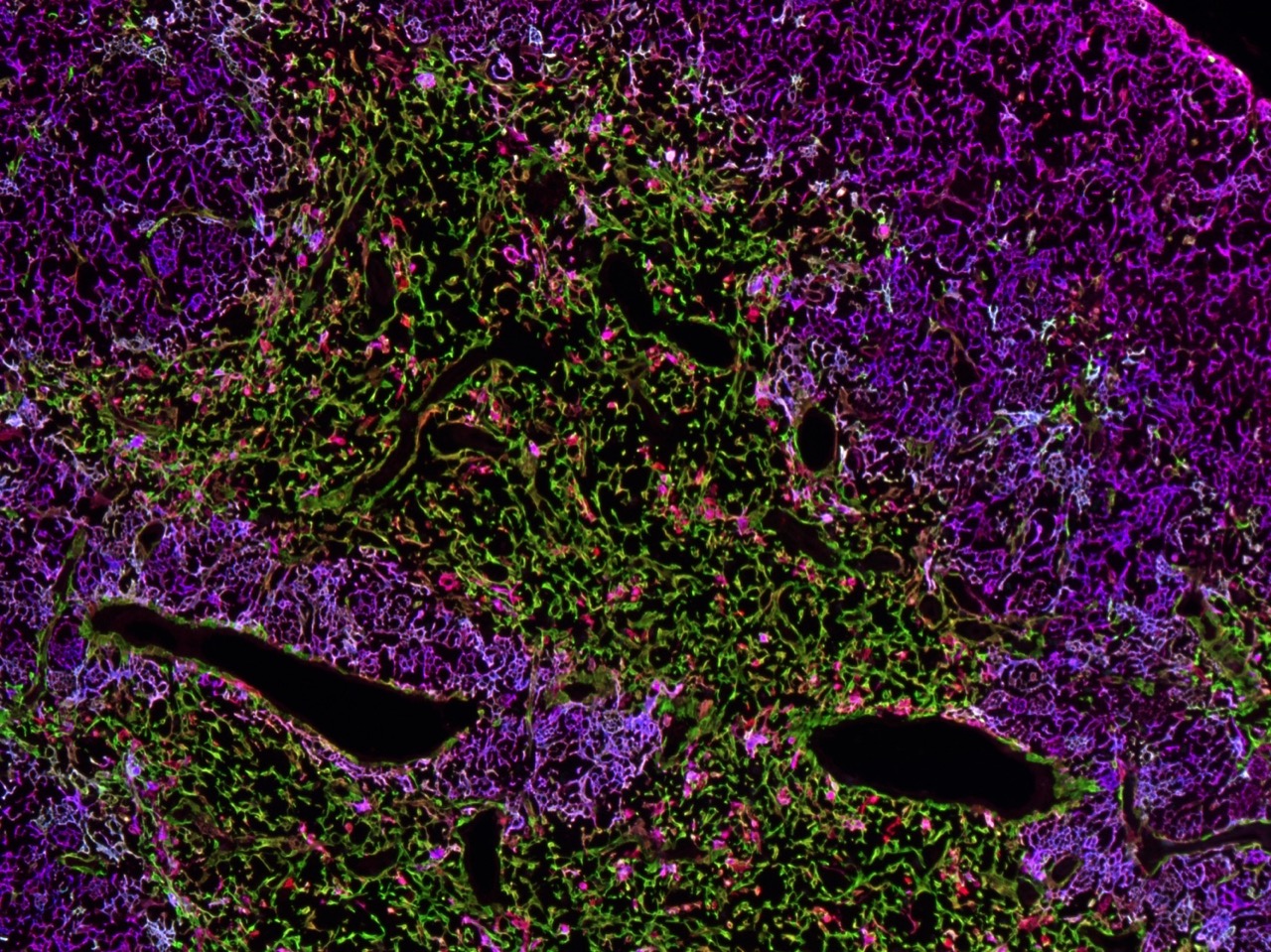

T cells develop in the thymus, an organ situated in the thoracic cavity just above the heart. The thymus doesn’t have an intrinsic source of self-renewing progenitors, and therefore, must recruit hematopoietic progenitors from the bone marrow.

Within the thymus, these progenitors, called thymocytes, undergo numerous developmental transitions, ultimately differentiating into naive T cells that migrate through the vasculature to seed secondary lymphoid organs, such as the spleen and lymph nodes. Naive T cells are master orchestrators of the adaptive immune response, protecting us from the myriad pathogens we encounter throughout life.

Thymocyte development is a tumultuous process in which ~95% of developing T cells undergo apoptosis. Self-reactive T cells are culled from the repertoire to prevent autoimmunity, while numerous thymocytes that fail to express useful antigen receptors are also eliminated.

The thymus undergoes profound changes throughout the lifespan. T cells output from the thymus early in life have myriad unique properties, such as an enhanced ability to proliferate and produce cytokines that promote pathogen clearance, along with an increased capacity to regulate autoreactivity. As we age, the thymus involutes, with a deterioration of the thymic stromal compartment accompanied by diminished T cell output. Age-associated changes in interactions between thymocytes and the thymic stromal compartment that alter T cell production and activity remain poorly understood.

Our lab is interested in understanding the molecular and cellular processes in the thymus that regulate generation of functional and self-tolerant T cells, and in determining how age-associated changes in these processes impact T cell differentiation and selection.